April 28th, 2014

During his lifetime, Rene Rivkin was a well known stockbroker and entrepreneur. His flamboyant nature meant that he was never far

from controversy. After being convicted for insider trading, serving a 9 month sentence of periodic detention and being banned for life from holding a stockbroking licence, Rivkin took his own life on 1 May 2005

The reason for the appointment

After his death, Rivkin’s executors ascertained that his deceased estate was not sufficient to pay his creditors. In particular, the

Australian Taxation Office had recently served a demand for approximately $21 million in respect of unpaid tax and penalties. That

demand arose out of a long running and high profile ATO and ASIC investigation into Rivkin’s business affairs including share trades

made through Swiss bank accounts.

On 7 November 2006, Rivkin’s executors applied to the Federal Court of Australia seeking an order for the administration of the

deceased estate under Part XI of the Bankruptcy Act. The Court made that order and appointed Anthony Warner of CRS Insolvency Services as trustee of the bankrupt deceased estate. From the date of his appointment, Mr Warner took steps to unravel the complex financial and business dealings of the late Rene Rivkin.

There was a particular emphasis on finding undisclosed or concealed assets that could be realised so as to be divided amongst Rivkin’s

creditors.

The administration of the deceased estate under Part XI of the Bankruptcy Act had 4 distinct stages which were as follows:

- The sale of Rivkin’s private watch collection.

- Recognition of the bankruptcy and litigation in England.

- Investigation of secretive share trading through Scottish partnerships.

- Investigation of and recovery from concealed offshore companies in Jersey

Sale of extensive private watch collection

During his lifetime, Rivkin maintained an extensive collection of Swiss watches. Many of those watches were purchased during the world famous annual Watch and Jewellery show in Basel, Switzerland. The watch collection was auctioned on-line by CRS Insolvency Services. The auction attracted a high degree of publicity and public interest. So far as we are aware, the auction of the Rivkin watch collection was the first time an Australian Insolvency Practitioner had conducted his or her own on-line auction without the assistance of an auctioneer.

The auction was a great success and generated sales well above valuation prices. All watches put up for auction were sold with the

most expensive watch drawing a bid of $20,200 (a Harry Winston men’s dress watch).

Recognition of the bankruptcy and litigation in England

Another iconic feature of the administration of Rivkin’s estate is its involvement in litigation in the United Kingdom.

In May 2007, Mr Warner, with the assistance of Ashfords LLP in England, applied to the English High Court for an order recognising the Australian bankruptcy proceedings as foreign main proceedings under the UNICTRAL Model Law. In light of the fact that the UNICTRAL Model Law came into effect in England only in April 2006, this was one of the first applications of its kind in the United Kingdom. The English High Court made the order sought, which greatly assisted Mr Warner in unravelling the complex structures that had been put into place by Rivkin and his advisors in the United Kingdom.

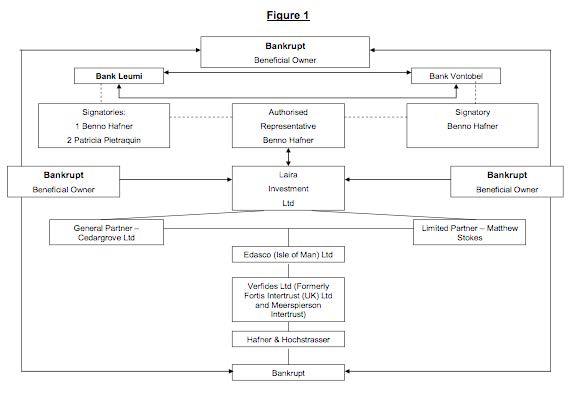

In August 2007, Mr Warner again applied to the English High Court under the Model Law (Article 21(1)(d)) for an order that Vefides

(a corporate services provider responsible for managing a relevant structure) produce copies of documents relating to the dealings

between Rivkin and various Scottish partnerships. While Verfides did not intend to oppose the application, a Swiss lawyer, Benno

Hafner, and his law firm, Hafner & Hoschstrasser (”the Intervenors”) applied to be joined to the application.

The Intervenors claimed to be interested parties within the meaning of Article 22 of the Model Law on the basis that they had a number of dealings with Verfides on behalf of 60 of its clients, and any disclosure of documents by Verfides to the Court may be in breach of the Intervenors’confidential obligations or an infringement of their clients’ right to respect for private and family life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

At the same time as Mr Warner’s application for the disclosure of documents, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission had brought proceedings seeking disclosure of the same documents (“the Mutual Legal Assistance Proceedings”). The Intervenors had a similar involvement in those roceedings. They eventually sought an order from the Court in Mr Warner’s proceedings that Mr Warner’s application be stayed until after the outcome of the Mutual Legal Assistance Proceedings. After a delay of almost 12 months, in May 2008, the English High Court refused to grant such stay and the matter proceeded to a substantive hearing to determine whether the documents ought to be disclosed.

At the final hearing, Ashfords LLP on behalf of Mr Warner argued that the Intervenors’ and their clients’ rights under Article 8 would not be infringed by disclosure of the documents. In the alternative, if it was found that the disclosure would infringe those rights, Mr Warner as Trustee in Bankruptcy was exercising a statutory function and, accordingly, such interference with the rights under Article 8 rights was justified under subsection (2) of that Article. The English High Court held that the rights under Article 8 would have been interfered with, but agreed with Ashfords LLP’s submission that such interference was justified in the circumstances: Warner v Verfides & Anor [2008] EWHC 2609 (Ch) (29 October 2008. It then made an order for disclosure of all the documents save for 7 pages which had been removed or redacted following confidential submissions to the Court by the Intervenors.

Complex dealings through Switzerland

The disclosure of documents and further investigations indicated that Rivkin used a complex structure of Scottish limited partnerships to trade shares anonymously using bank accounts maintained in Switzerland. A Scottish partnership is a different concept to a general partnership in the sense that the partnership or “firm” is treated as a distinct legal person separate from its members. Further, the liability of partners differs in that a Scottish partnership can consist of general partners who are liable for the debts and obligations of the limited partnership and limited partners whose liability is limited to the extent of their capital contributions. Management functions are exercised by the general partners and a limited partner is unable to take part in or otherwise interfere with the management of the partnership.

The partnership and banking practices were established to conceal Rivkin’s beneficial ownership of the funds and assets within the

structure. The anonymity afforded by the structure allowed Rivkin to trade shares for many years without such trades and resulting

profits being linked to him by the Australian authorities. It was not until the ATO and ASIC conducted their detailed investigation that the full extent of Rivkin’s secretive trades came to light. The tax assessments and penalties that flowed from the investigation was the main impetus for approaching the Court for administration under Part XI.

Mr Warner was able to use his position as trustee of the deceased estate to obtain information that was not available to the regulators during the course of their investigation. CRS appointed Swiss auditors to review Swiss bank accounts linked with Rivkin. CRS also appointed an investigator on the ground in Zurich to conduct discreet inquiries in relation to Rivkin’s affairs. The work on the part of CRS paid off when transcript of a confidential compulsory interview conducted by the District Attorney of the Canton of Zurich came into the hands of Mr Warner. The interview arose out of allegations that a bank manager employed by Bank Leumi (an Israeli bank based in Zurich) embezzled funds held in Bank Leumi accounts or otherwise transferred such funds without authorisation. The banker, Mr Ernst Imfeld, alleged that Rivkin had created documents that were partly forged relating to share and currency transactions.

The interview was conducted in December 2002 and Rivkin soon admitted that he controlled the accounts held in the name of various Scottish partnerships and was the controlling mind of the partnerships themselves. Rivkin testified that the Scottish partnerships maintained accounts with Bank Leumi. When Rivkin wanted to trade shares anonymously, he would purchase shares on the Australian Stock Exchange (and markets around the world) in the name of Bank Leumi and the bank manager. On notification of the purchase, the manager would automatically attribute the shares to the accounts of the Scottish partnerships. The bank manager established portfolios with each of the accounts.

Rivkin would only contact the bank manager if the shares purchased were in fact purchased for or on behalf

of Rivkin’s associates. If that was the case, the bank manager would allot the assets to the relevant portfolios within the account.

Imfeld’s unauthorised transactions affected, amongst others, accounts held in the name of Rivkin controlled Scottish partnerships.

Accordingly, Mr Warner took the view that proceedings should be brought in Switzerland to recover the funds that were misappropriated by Imfeld. The Swiss auditors appointed by Mr Warner were able to establish that approximately AUD$2,780,000 had been misappropriated by Imfeld and he admitted to same. The Swiss auditors also identified further suspected unauthorised transactions amounting to AUD$7,910,000. Imfeld was convicted of the fraud in 2008 and received a sentence of 8 years imprisonment. The Court found that Imfeld had misappropriated at least AUD$175,000,000.

In December 2010, Mr Warner commenced proceedings against Bank Leumi in the Commercial Court of the Canton of Zurich on behalf of the bankrupt estate and the Scottish partnerships maintained by Rivkin. The purpose of the proceedings was to recover monies misappropriated by Imfeld. Mr Warner experienced high barriers of entry to the Commercial Court. For instance, the Court filing fee alone amounted to approximately AUD$240,000. Cases in the Commercial Court are ranked in priority based on the quantum of the claim and the importance of the matters at stake. Cases involving significant amounts of money and issues of high importance are fast tracked through the system notwithstanding the date on which they were filed. The system also involves a number of preliminary hearings where the parties are encouraged to mediate. At such preliminary hearings, the judge will have read the papers and their assistant would have written an advice on the matter. The judge then gives a preliminary opinion and indicates what the likely outcome will be if the matter proceeds to a full hearing. If the matter does proceed to a full hearing, the judge that conducts the preliminary hearing also presides over the full hearing. When the first preliminary hearing is finalised and if the matter is referred to a full hearing, the Commercial Court requires a retainer to progress the matter further. In this case, the Commercial Court required a retainer of between approximately AUD$175,000 and AUD$233,000 to write and issue judgment in the matter. It was estimated that the judgment would be available between 12 to 18 months after payment of the retainer. The Swiss proceedings were settled in December 2012 for an undisclosed sum.

Concealed offshore companies in Jersey

In the course of the administration, Mr Warner conducted public examinations. As a result of the information disclosed in the examinations and further evidence found in the course of his investigation, Mr Warner formed the view that Rivkin was the beneficial owner of funds held by a company known as Thameslink Limited. It was apparent that Thameslink was registered and maintained bank accounts in the Bailiwick of Jersey, a British Crown dependency located off the coast of Normandy, France.

During his investigation into the affairs of Rivkin, Mr Warner interviewed various employees and associates of Equity Trust, a corporate services provider in Jersey responsible for managing Thameslink. Those interviews made it clear that substantial funds were held in Thameslink’s Jersey bank account. Despite requests by Mr Warner, Equity Trust did not confirm that they would freeze the Thameslink accounts of their own volition pending proceedings being brought by Mr Warner to recover the funds. Fearing an imminent risk of dissipation of the Thameslink funds, Mr Warner retained Ashfords LLP (UK law firm) who were assisted by Hanson Renouf (Jersey law firm) to apply for a freezing order and an order for disclosure of all documents relating to Thameslink and its accounts within 24 hours. Those orders were granted.

Jersey is not and never has been a signatory to the UNCITRAL Model Law. Under the laws of Jersey, it is open to the Courts to have

regard to the operation of the Model Law in insolvency proceedings, but the Model Law does not actually apply. The recognition of

foreign bankruptcies and provision of judicial assistance in Jersey is therefore wholly discretionary.

To leap the hurdle posed by the laws of Jersey, Mr Warner applied to the Federal Court of Australia for the issue of a letter of request by the Federal Court to the Royal Court of Jersey seeking that the Royal Court act in aid of and be auxiliary to the Federal Court in relation to the Rivkin bankruptcy. The purpose of the letter of request was to seek recognition of the bankruptcy by the Royal Court and obtain assistance in the recovery of funds held by Thameslink. The letter of request was issued and the Royal Court agreed to act in aid of and auxiliary to the Federal Court (Warner, in the matter of Rivkin [2007] FCA 2020). Subsequent investigations revealed that the Thameslink accounts held AUD$3 million, being the proceeds from the sale of Rivkin’s luxury motor vessel, the Dajoshadita. As Mr Warner was able to demonstrate to the Royal Court of Jersey that Rivkin was in fact the beneficial owner of the funds, the Court ultimately ordered that the funds held by Thameslink be paid over to the bankrupt estate for the benefit of creditors. That was particularly gratifying as the executors were not aware of the existence of Thameslink or the cash at bank following the sale of the vessel until Mr Warner had performed an in depth investigation into the affairs of Rivkin. The administration was a success for creditors and they were paid a dividend of 11 cents in the dollar on claims totalling AUD$26.68m.